My grandmother used to tell me stories about her childhood, in the 1920s, which were both exotic and relatable. She was only 45 when I was born, which seemed ancient to me, of course, but now I know that the half century mark is prime time for reflection and reminiscing. We are unreliable narrators of our own lives, and the charm of her mischievous and adventurous early years in the small provincial town on the Volga remains the biggest shared treasure of our fraught relationship.

Now that I am the age that she was when she was raising me, I realize how memory shifts as time goes by. In her telling, she was a spirited and inquisitive child that was frequently in trouble with her humorless but loving parents. The irony that these were the qualities she most deplored in me escaped me then. I also bought into this portrayal of her parents for the time being, while years later it came to me that perhaps the character trait she most chose to emulate—grim rigidity—was the least praiseworthy attribute of this couple. They never seemed quite real, just shadows of semi-forgotten ancestors, even though less time separated my childhood from them than from today.

I recently read “People Love Dead Jews” by Dara Horn. In this book, which had me both nodding in agreement and holding my breath, I came across a chapter about the Jewish community in Harbin in early 20th century. I do not know if more is written about this place and time in history, but this was the first time I gasped in recognition: “Papa taught Hebrew in Harbin”. For among grandmother’s stories was always this nugget: her father spent several years in Harbin, teaching Hebrew to children while his brothers were running a business there. This has always been just a naked, stand-alone fact, and when I was a child, it always seemed like enough information. Great-grandfather, whom no one in my world besides grandma and her brother ever met, for he died before The War and before she left her hometown that neither my mom nor I ever even visited, was always described as a stern disciplinarian and seemed sufficiently boring to not merit additional investigation. But grandma’s own childhood memories of her father speaking Chinese to make the neighborhood kids laugh echoed my own delight when her brother, my beloved great uncle, would pretend to speak Chinese to me. I knew he was faking it, but he was so delightfully comical!

I finally learned that this interlude in great-grandfather’s life was not random, as I always assumed without additional thought. Fortunately for me and mine, his ultimate fate was arguably better than that of many of the people he would have known in Harbin—and that is saying a lot, considering that he returned to his hometown of Lyozna, Belarus [1] (at some point before getting engaged to my great-grandmother on June 12, 1919 in Vitebsk[2]), got married and had two children, lived through the darkest years of Stalinism, and died before he was 60 in 1940.

I have been an immigrant since I was a teenager. I have traveled. I spent two summers in Europe, and I have been to China on a work trip, to the beautiful and sophisticated Shanghai, which is actually nowhere near Harbin and has a completely different history. Every day of my professional life, I talk to people who have, at a minimum, spent several years in a foreign country. Until now, I have not thought of this remote, unknown man’s journey, his years (how many?) in a much colder climate, in a completely different world. I never imagined that he had his own “stranger in a strange land” journey.

As a child I did not know enough about the world to imagine China at the beginning of the 20th century. I never gave a single thought to how great-grandfather traveled so far—and back—what kind of business these nameless brothers of his had, why and when did he return to Belarus, eventually making his way to and settling in Russia proper. My grandmother was not a person who did not talk about the past, but I do not know how much she knew about that period of her father’s life. Somewhere along the way, there was some falling out with these uncles that severed the family ties for all eternity (they were not welcome to attend their brother’s funeral). It might have been related to this business in China, but grandmother’s own mother never told her. In those days, people did not ask; children did not question their parents. It is nearly impossible for me to understand the respectful yet reserved, affectionate yet distant relationships of that bygone era. To the families of these great-uncles, whoever and wherever they are, my family is the missing link, the lost tribe. Do their descendants remember today that there was another brother, another uncle? Is this Harbin interlude a part of their family lore? Sometimes I lament the loss of family memories to family feuds on top of the already precarious and unreliable way history was treated in the Soviet Union. Other times, I concede that maybe it is only natural that the lives of ordinary people do not survive generational memories.

Dara Horn’s book gave me an unexpected glimpse into my great-grandfather’s unknowable life. There is a connection that survives time and space, and a memory that is a blessing.

זיכרונו לברכה אַבְרָהָם

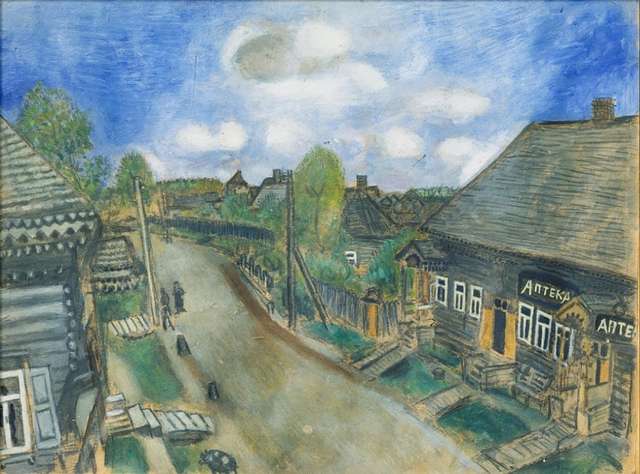

[1] The birthplace of Moishe Shagal, aka Marc Chagall. I wonder if they knew each other? They would have been contemporaries.

[2] The only exact date in this narrative, because my great-grandparents’ engagement announcement somehow survived time and distance, and I treasure it.