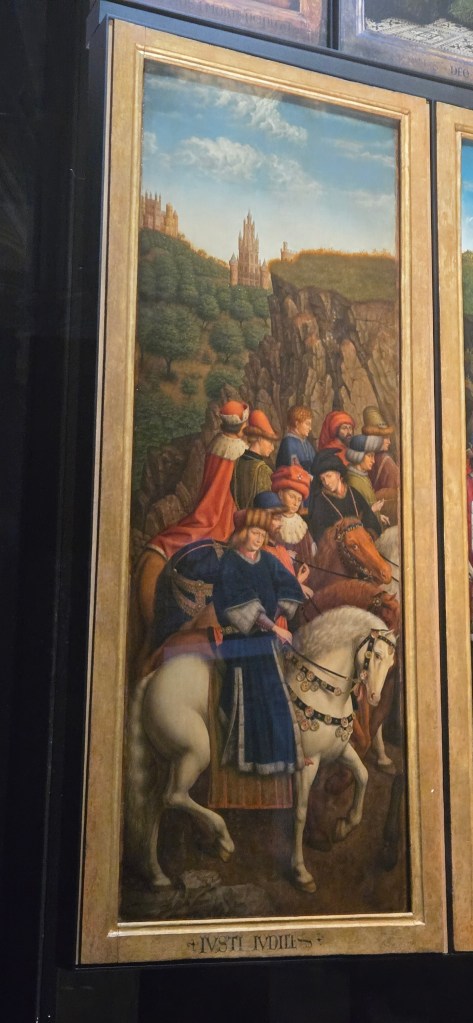

My return to Belgium was not prompted by any nostalgia https://oldladywriting.com/2025/11/23/whats-in-belgium/ but by the last piece of art from my Bucket List–the Ghent Altarpiece, aka the Adoration of The Mystic Lamb. As a child, I read a book called “Pelike with a Swallow” by Anatoliy Varshavsky, in which each of the 12 chapters is dedicated to a particular art mystery, from ancient to modern times, starting with the self-same pelike and ending with Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais. I might add that I have now seen nine of these art works, excluding one Rembrandt in Stockholm, one portrait in Russia, and a bust of Flora that, as of the writing of the book in 1971, was attributed to Leonardo but half a century later was conclusively proven to be made in the 19th century by an English sculptor. I might just quit while I am ahead, for how can one top The Mystic Lamb? Even since I learned about it, I have been haunted by its reputation as the most stolen work of art in history and by the fact that one of its panels remains unrecovered to this day.

Ghent seemed the most Dutch of Flemish towns, and the least sunny day of the week contributed to the comparison. There is still enough whimsy, including this thing (a weather vane?) and Gravensteen Castle, where the audio guide offered either a straight history or a humorous version thereof. Spouse and I both elected the latter, and it was an overload of bad jokes. More audio guides should have this option.

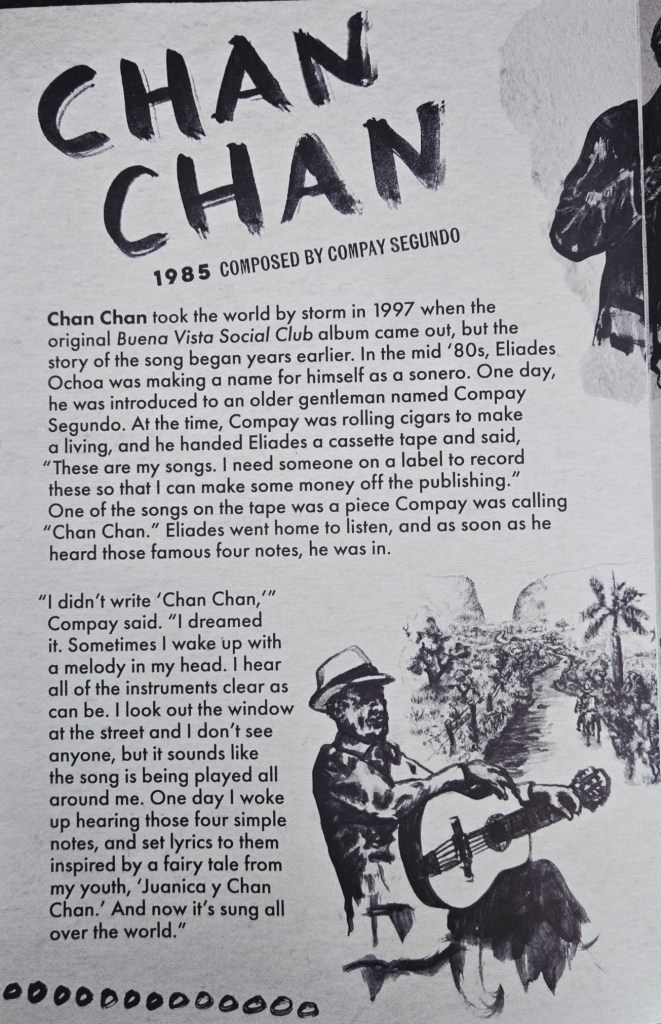

At St. Bavo’s Cathedral, we were first treated to an interactive 3-D presentation on the history of the altar which was pretty cool but for an extremely annoying virtual cauldron who led the way from one exhibit to another. The fear of banging into that thing, never mind that it was not corporeal, created a fair bit of unnecessary tension and distraction. Just go straight to the Sacrament Chapel and enjoy The Altarpiece. I have no words to describe it…

I could not miss visiting my old friend Brugge, though I did not recall that the walk from the train station was quite so long, or that the Belfort was not really visible until you are pretty much under it. From the art scene, it is home to the Madonna of Bruges, the only statue of Michelangelo to leave Italy during his lifetime and subsequently stolen by the same villains as The Ghent Altarpiece—Napoleon and the Nazis. Otherwise, Brugge has two fabulous breweries, De Halve Maan and Bourgogne des Flandres. That’s the best part about Belgium, really, that balance of admiring great art and architecture and then taking a lovely break with delicious beer. I bought no lace doilies this time.

I still found Belgium quite lively and warm, in spirit if not in actual temperature. Brussels is a raucous delight, especially during the Christmas market season. In fact, the town’s and possibly country’s biggest fair opened three days after our arrival literally at the front door of our hotel. It was the best surprise ever! The second best was that, despite being advertised as a bilingual town, it is a French-speaking one. Not only did I not need to subject anyone to my atrocious attempts at Dutch, but also did not need to resort to my best foreign language, English.

My mother has been saying that her main reason for wanting to visit Brussels is the Magritte Museum. Well, we differ in many ways. The only painting of his that I recognized there was The Empire of Light, and that was only because my next-door freshman dorm neighbors had a poster of it on their door. The man with the apple face is not there, although the giant green apple sits on the roof, misleading visitors. I feel like it is best to just listen to the Paul Simon song “René and Georgette Magritte with Their Dog after the War”. The adjacent Oldmasters Museum is more my speed, with some particularly wild Bruegels and Boschs. I may not know much about art but I know what I like, as John Cleese famously said to Eric Idle.

As far as culinary delights, there are many in Belgium, but the greatest of these is chocolate. I like it. Moreover, I believe in its medicinal qualities. I partake daily. But, the number of chocolate shops in Brussels was so overwhelming that I ended up basically paralyzed with indecision. I bought one sampler at a place called La Belgique Gourmande, set foot into the first ever Godiva store (bought nothing), and ultimately loaded up on Lindor truffles, which are not even Belgian. We did purchase a bag of traditional Belgian candies called Cuberdon, sugary triangles with gelatinous filling. They are not unpleasant, but can only be tolerated in small doses and not often, given their exceeding sweetness. It is no surprise at all that they are not known outside of Belgium.

Since I went to Portugal the first time and did not try any port https://oldladywriting.com/2020/11/29/o-fado/, I make it my business to drink the local beverages of choice and fame. In Belgium, it is a no brainer, for it is the land of beer, though honorary mention goes to the Filliers whiskey, which, coincidentally, was the winner of my annual whiskey advent calendar last year. I rooted so hard for it, but truth is truth—of the 24 samples, it was the best, the smoothest and the most delicious.

I learned to drink beer in Ireland, and Guinness remains the gold standard. It is the perfect beer, and any negative comments on this topic will be deleted. Belgian beer, nonetheless, is still flavorful and delicious. I consumed significantly more of it than chocolate, which is to clarify, a pint or two at lunch and dinner, with no ill effects and great enjoyment.

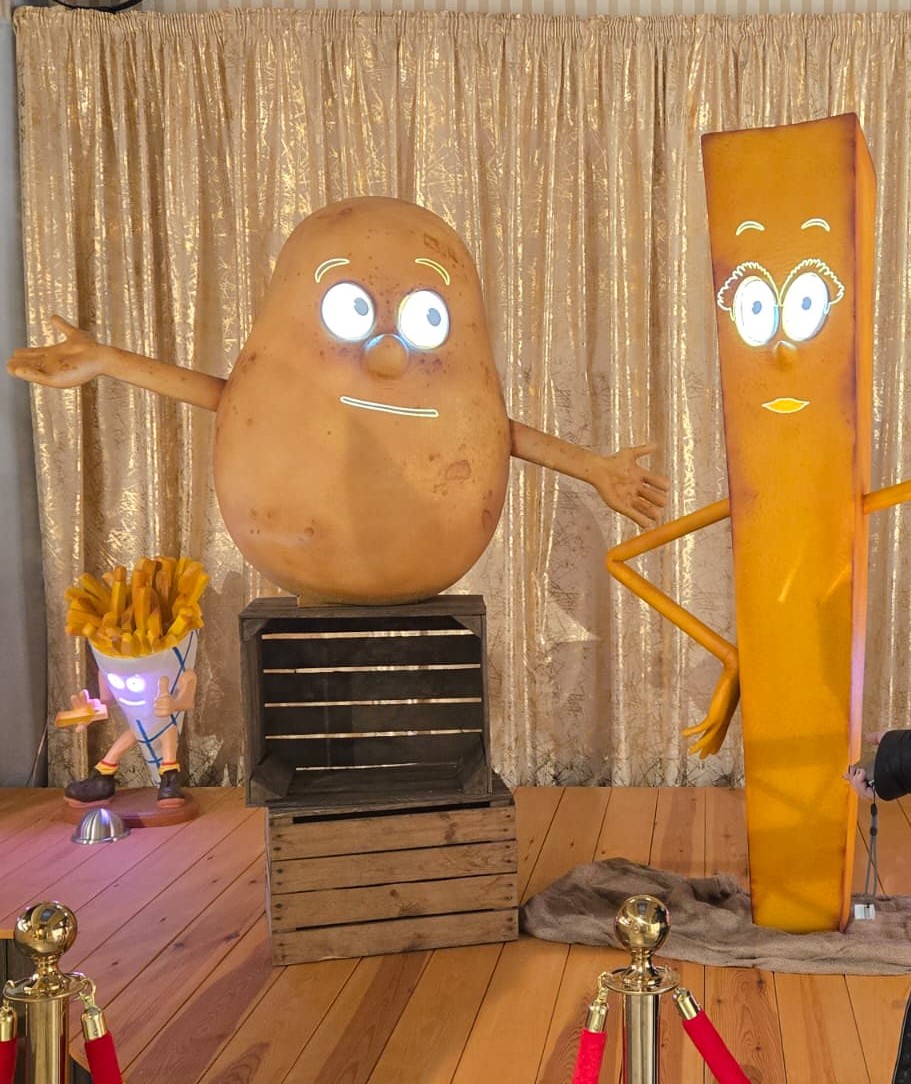

Beyond beer and chocolate, Belgium is home to two culinary creations: Belgian waffles and what should be called *Belgian* fries, or frites. I am inclined to side with the Belgians regarding the invention of the latter, as their neighbor to the South has enough gastronomic clout. The Frites Museum was a really good time. Not only was it informative and interactive, but the price of admission included a cornet of actual traditional fries at the end. Ask me what I got at the Magritte Museum—so it is pretty conclusive which is the superior place to visit.

I made the same mistake with the waffle as I did when I first came to Koksijde all those years ago, getting the one smothered in chocolate sauce and loaded with other toppings, including a chocolate Manneken Pis. It was overwhelming, and the experience lasted me the entire vacation, possibly beyond.

And speaking of Manneken Pis. I understand he is possibly as much a target for thieves and vandals as the Altar of Ghent, and apparently the little statue to which the tourists flock these days is a replica. Spouse and I visited him at least daily during our stay in Brussels to check what outfit he was wearing, and also sought out Zinneke Pis (the dog) and Janneke Pis (the girl). Admiring some of the world’s greatest art as well as hunting down the sculptures of various urinating creatures—this trip had it all!

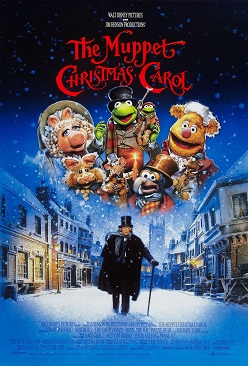

I could not identify even remotely any street in Brussels on which I might have walked to the hostel with my roommate all those years ago. I remember only that it was the cleanest room we had during our wanderings, which is saying exactly nothing. And I did not make it back to Antwerpen. On the flight home, I rewatched “In Bruges” and “The Monuments Men”, so different from each other as well as from my actual lived experiences during my week in Belgium, yet somehow relevant and a perfect coda to a great trip.