“Oh, Havana, I’ve been searching for you everywhere

And though I’ll never be there…”

(Billy Joel, “Rosalinda’s Eyes”)

In 1997, I prepared my first list of places I wanted to visit in this lifetime. It was pretty basic, containing about what you would expect (although even then, my focus was primarily on Europe). The list was revised several times in the intervening years, and I am currently working off the most current, 2020 version. It is significantly more precise (I narrowed New England down to Maine, identified specific cities and experiences in various countries which I have already visited, and ultimately, decided there is nothing for me in either Minnesota or Australia—no offense). The place at the top of this new[ish] list is Cuba. In 1997, I did not imagine that visiting Cuba was possible. It seems complicated still (especially for someone with my aversion to organized group travels, and given the general state of the world). But everyone has to have that one place that remains elusive.

When I was in second grade, the mother of one of my classmates did a presentation to our class about her trip to Cuba. Bulgaria was exotic enough. Cuba was unimaginable. She came with a show and tell. There must have been some candy, though I have absolutely no memory, real or imagined, of that, and have no experience with Cuban treats to this day. There must have been some elementary-level geo-political presentation; we already felt a certain reverence for our exotic, far away only friend in the Western Hemisphere. What I do remember very vividly is a little stuffed crocodile that she brought with her. I am sure that a baby taxidermy croc would intrigue any child; it was so fascinating to me that in my mind’s eye, I still see Irka Rybakova’s mother standing in front of our class in her belted dress, holding this shiny leathery wonder. Neither alligators nor crocodiles exist in Russia; this was years before I saw one in a zoo. So strong was this impression that for years if I heard “Cuba”, the first image that would come to me is that of a little crocodile.

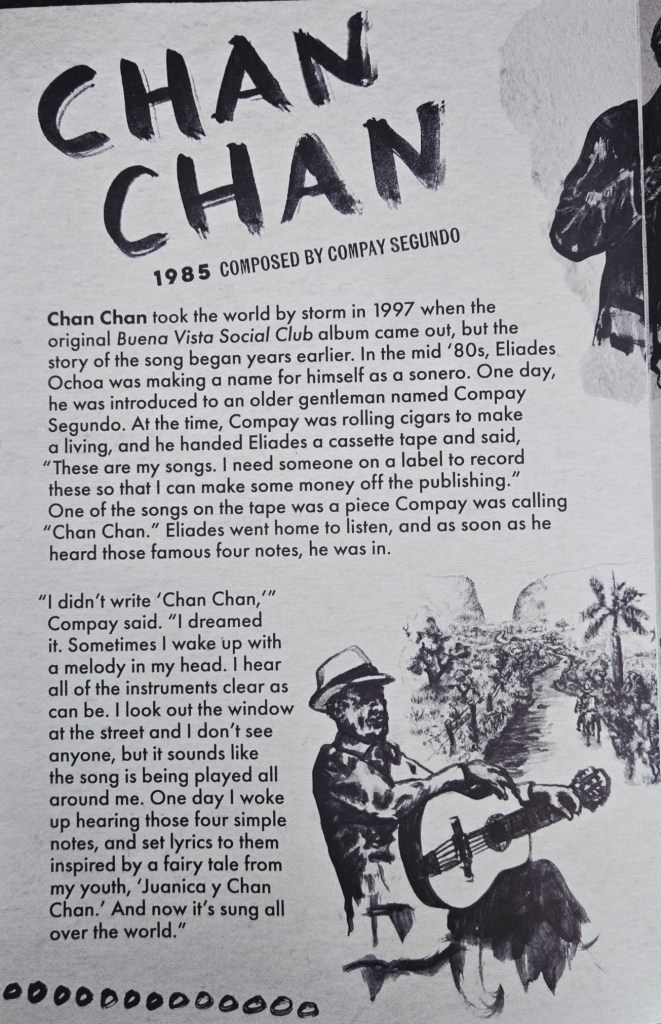

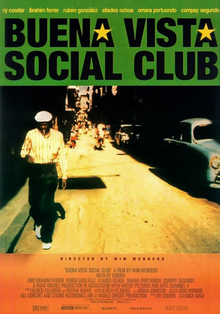

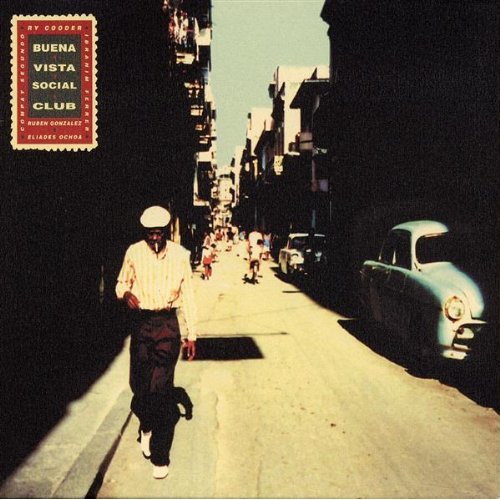

That is, until I saw a documentary on PBS[1]—and that day is about as far away from today as it is from the day I saw the baby crocodile, which is to say that I have identified Cuba with its marvelous music for at least as long as I have identified it with crocodiles, a distinct improvement. The film touched me on every level—I did not just fall in love with the music, but the sights of Havana, the camaraderie of old musicians, their unpretentious yet assured personalities, their warmth and pride in their homeland[2]. From that time until CDs have gone the way of cassette tapes, I have accumulated a lovely collection of traditional Cuban music. My meager Spanish is just enough to get the gist of most songs, and that is indeed enough for me. At some point, the Buena Vista Social Club orchestra came to town during a worldwide tour. I did not go (something about ticket prices, and I am generally not a concert goer). While it is tempting to call this the biggest regret of my life, it did not feel so at the time. The CDs continued to sustain me.

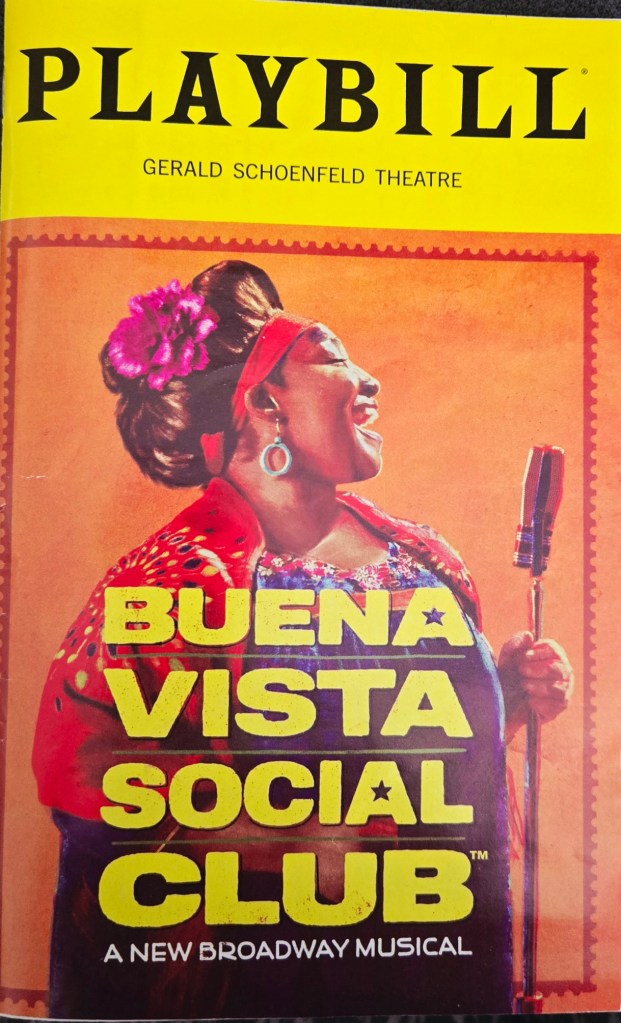

Almost two years ago, Buena Vista Social Club musical showed up off Broadway, but it was December, and I had other plans. Once again, I made an informed decision to hold out. This time, I was not wrong, for a little over a year later, it finally appeared on The Great White Way, and I was there for it. Well, to be honest, I was not the first in line. I was skeptical. When you love something, you do not want it touched and tinkered with. You do not want your memories sullied. This is why I avoid movies based on books I love[3], and generally try to avoid musicals based on movies, which these days is practically an impossibility. My mother and I planned a trip to NYC, and I was still not convinced, thinking that I will grab the tickets when I get there. Then Buena Vista was nominated for a Tony, and I figured I better make a move before it becomes a hotter ticket than my limited window of opportunity could support.

I loved the music, but knew nothing about the story, or even cared about it. On the night of the Tony Awards, I instantly recognized all the characters during the musical number as if they were old friends. I figured, if nothing else, I will still love the music. I have seen jukebox musicals, some with better books than others, and in all cases, the music alone has been enough.

It turned out to be the story I did not know I needed. The prequel to the events of the documentary, when Omara Portuondo met Ibrahim Ferrer, Compay Segundo, Ruben Gonzalez and others, when they were all making music in the waning days of the Batista regime and the dawning of the revolution, is full of hope, exuberance, and excitement, and sparkles with gentle humor. The reunion of the former bandmates several decades later, familiar from the documentary, is wistful and burdened with the weight of years gone by, as these things go. Through it all, the musicians—recipients of the most well-deserved special Tony Award—are simply spellbinding, and the songs are just as gorgeous as ever I heard and loved them.

And then there are the Portuondo sisters. On the eve of the revolution, one leaves for the U.S., in the scene reminiscent of another musical, on seemingly the last plane out of Havana. The other stays, because someone has to continue to sing the songs of the people, for the people. The moment when Omara decides not to leave, whether based in truth or in romantic fiction, touched my heart even more than hearing Chan-Chan live. Some choices we make, some are made for us, some are conscious and based in sacred truth, some are based on the cards we are holding at the time. Sitting in the Schoenfeld Theatre on a Friday night in July, seeing and hearing this story with all my senses, I both cried for and praised the impossible, life-altering, life-affirming decision[4]. https://buenavistamusical.com/

[1] When we still had PBS…

[2] The Mandela Effect had me believing all these years that Buena Vista Social Club won the Oscar for best documentary. It did not. The documentary that won that year was “One Day in September”. Do you remember it? Me, neither.

[3] No, Les Miserables does NOT count, because I saw the French TV special first, for those reading [all] along.

[4] I once had a classmate of Cuban heritage. His father fled to the US during Batista’s rule; his mother, during Castro’s. He marveled at the idea that had they never left Cuba, they would have never met, being from such different socio-economic background. The conclusion that I drew from this story, however, was that people flee various regimes for various reasons, not just the ones from which we are taught to believe they do.