One of the main villains of my raucous childhood was one Shturman. This was, and is, his real last name. I am not changing it here because (1) he is not likely to read this, (2) this unusual name[1] is too much a part of him, and (3) every word is true.

Shturman’s code name was “Douche”. No, listen, in Russian, it just means “shower” (and in French as well, but we did not know it then). And the reason he was “Shower” was because we called him “D.Sh.”, which stood for “Durak Shturman”, which means “Shturman the Fool”. So it all fits together rather beautifully. Since “fool” was the worst insult we knew, literally everyone’s code name started with “D”, but this was the only one that is not lost in translation[2]. At school, he was known as “Shturm Zimnego”, or “Storming of the Winter [Palace]” (the event that, according to what we were taught at school, started the Great October Socialist Revolution), but we did not feel that he deserved so much honor.

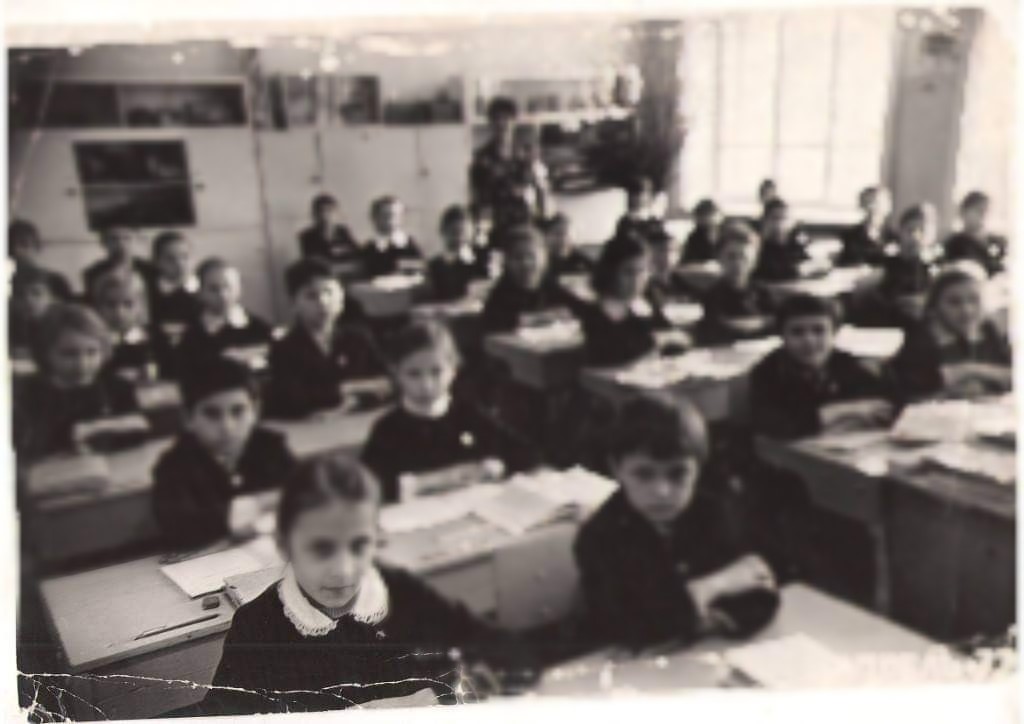

My BFF and I met him on the first day of school, September 1, 1975. In fact, we all met each other for the first time that day. It was not a good day for me, for it started out quite literally on the wrong foot. All the girls were wearing pretty summer sandals (my friend’s were pink). I, as was my lot in childhood, was wearing heavy, hideous black/brown booties. I was perpetually overdressed in childhood by my overprotective grandmother; I always had a couple more layers on than anyone else. My mother, who gets incredibly defensive about every single choice made for me not by me, would undoubtedly say that prettier shoes could not be found—and that would be a lie. Everyone else wore common Soviet-style sandals readily available at any children’s clothing store in town. My ugly orthopedic boots were imported. And to top it all off, the trend of sending me off on the first day of school with a bouquet of chrysanthemums for the classroom teacher started that unfortunate day. You guessed it—everyone else had lovely summer flowers. I yearned for daisies, and cannot abide chrysanthemums to this day. But I digress.

Mine and my BFF’s mothers and both of Shturman’s parents went to high school together. Their paths diverged for a few short years after college and joined again on that day when it was discovered that they had children born in the same year (two in January, just a week apart, and one in November), who will be starting school not just at the same time, but at the same school and in the same class. Of course, given that our parents were friends, we were thrown together a lot in those early years, for all the holidays, all the birthdays, summer trips to the countryside, etc. Well, since I lived with my grandparents, I was not allowed to celebrate with my friends, so that was one very small benefit, having a bunch of 50+ year olds rather than Shturman over. And since I was born in November, I did not have to share my birthday with him, only with the October Revolution, celebrated in November according to the “new”, Gregorian calendar.

To commemorate the Revolution, we got a few days off from school—basically, our fall break. In that place and time, it was common to gather for all festivities. One year, when I was maybe in second grade, we all met at my BFF’s apartment. The adults, which consisted of Shturman’s parents and mine and my friend’s mothers (both divorced, but with or without boyfriends—memory fails) went for a walk. Do not be shocked, it was a kinder, gentler time; neighbors looked out for each other and each others’ kids. And it turned out that the real danger lurked within…

The adults departed for their nighttime stroll, and BFF and I hoped to have some fun: sing along to Soviet pop music with pantyhose on our heads, make plasticine animals, read about astronauts and plan our own future space adventures—really, the possibilities were endless. It was a Soviet studio apartment: one room, bathroom, and a kitchen at the end of the hallway. We staked out the kitchen. Shturman pestered us for a bit, at one point brandishing a bottle of wine[3] and boasting that he can drink it all. We called his bluff with all the disdain we could muster; predictably, he did nothing but buzzed off to the room. But our little gray cells were already activated.

As children, we were told that alcohol is poison. As we saw adults drink copious amounts thereof, the unspoken assumption was that it is poison specifically to children. Which budding sociopath came up with the cunning plan of serving tea laced with alcohol to our arch enemy shall remain undisclosed. I know that “Hey, Shturman, do you want some tea?” was not spoken by me. He and I were never verbal with each other, letting our fists do the talking.

My friend made him a cup of tea, which was actually mostly vodka. Shturman, clearly feeling very pleased with himself and his imaginary superiority over us, took a sip, immediately choked and started coughing, eyes bulging. You did not see this coming, right, because you thought Russians drink vodka from birth, and I am here to break down the stereotypes. He dropped the cup, and there was that moment in which you know things can go either way—and this is how they went, with him screaming “I will kill you!” and us shrieking and running. Studio apartment, where are you going to go? Bathroom, of course—the only place with a lock.

Shturman started pounding on the door and screaming, “Come out or it will be worse for you! I will break down this door!” BFF was sort of turning on me: “So, alcohol is poison, huh? He is alive and well, and even worse than he was!” I was just hoping the door will hold, and besides, it was a modern apartment, with a “combined” bathroom, meaning toilet, sink, and tub were all in the same place. We had all the conveniences, and could wait him out until our parents’ return. Eventually our enemy calmed down and walked away, and we settled in the bathtub, lulled into a false sense of security.

Suddenly, a scratching sound alerted us to a new potential disaster. Shturman procured matches and started lighting them and shoving them under the door. He decided to smoke us out, that weasel! But the joke was on him—we had access to plenty of water, and started pouring it on the matches, having emptied the toothbrush glass for this purpose. Neither side was going to surrender, but we assumed that the matches will run out before water. As luck, good or bad depending on perception, would have it, adults came home before either, to a minor river in the hallway, with purses and shoes floating by.

We refused to leave the bathroom until the Shturman family departed. I remember nothing of the aftermath of this event (not even the last of its kind), beyond never getting along with this Shturman until I left the country several years later. I have not seen him since. Wherever he is, I hope he is not holding a grudge.

[1] It literally means “navigator” in Russian. Unusual and kind of cool, if one stops and thinks about it.

[2] For example, we referred to Shturman’s father as “D.P.”, i.e., “Durak Papasha”, meaning “Dad the Fool”. We disliked him because his son looked just like him, and we never saw him as anything other than his son’s father. Yet DP was the only father that was present in our group of friends. Something to unpack here.

[3] Again I remind you, different time, different place, no burden of Puritan heritage.

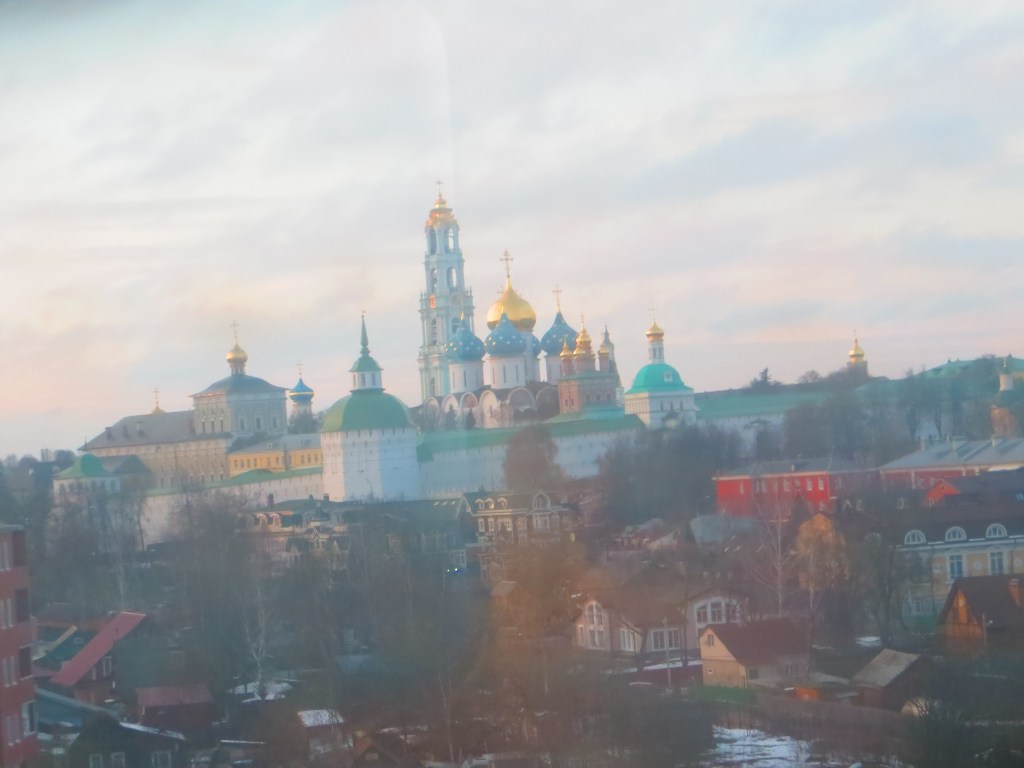

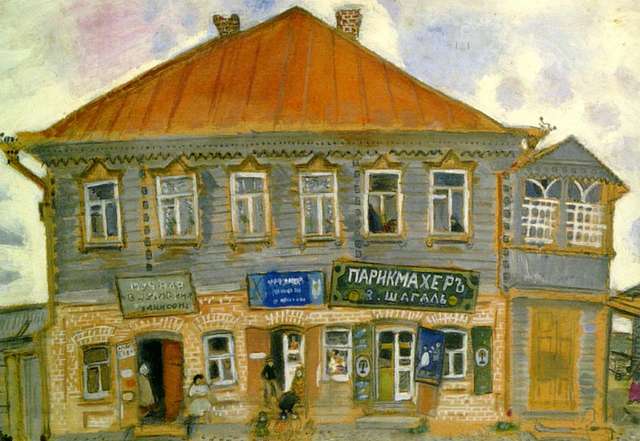

(I found this on GoogleMaps)

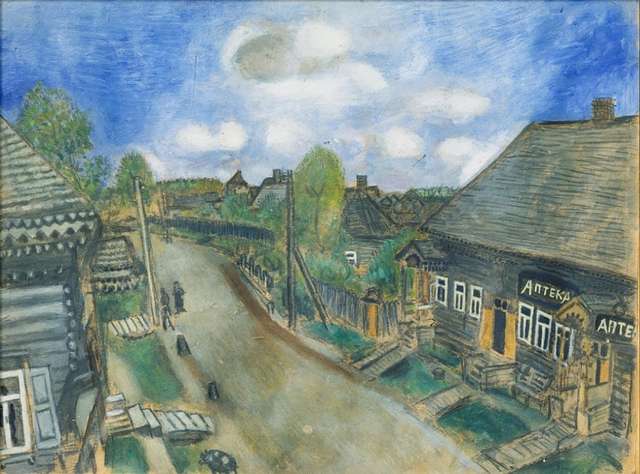

(I found this on GoogleMaps)

What we thought we were getting versus what we got (not actual photos).

What we thought we were getting versus what we got (not actual photos).