One of my most favorite childhood memories is when I served as Honor Guard at an election. I have forgotten a lot of the particulars about what, how, why, and even when. Frankly, I do not want to ask for corroboration, because I am almost afraid that my friends’ memories are not as glorious as mine.

“I’m no expert, but I remember reading somewhere, every time you retrieve a memory, that act of retrieval, it corrupts the memory a little bit. Maybe changes it a little”[1]. Well, this particular memory has probably been retrieved to the point beyond recognition, for the joy brought by the factual experience of it as well as for the sheer uniqueness of the experience. Observing an election in the Soviet Union, a state that officially only existed for 70 years (75 if you count from the Revolution)! From the inside! Had I known how soon it was going to end, for me AND the country, I would have tried to remember more and better. But how?

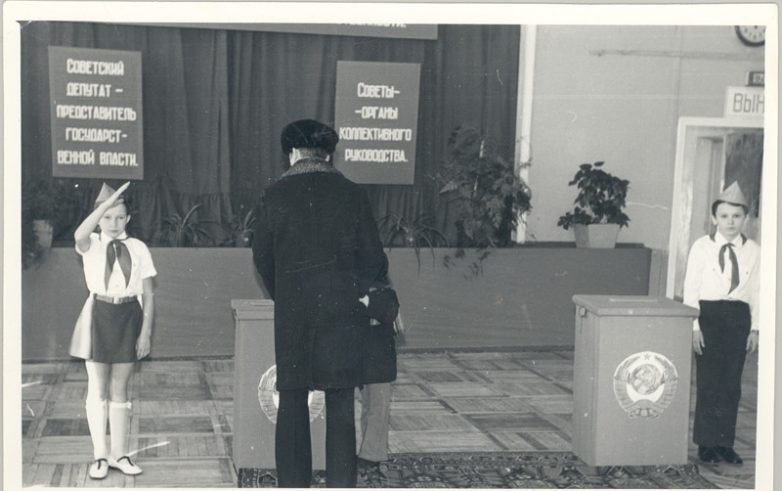

And so, in the year I cannot name with any certainty other than it was in the late ‘70s, our classroom teacher, a particularly unpleasant personage who ostensibly taught us, badly, algebra and geometry, announced that our class was chosen to serve as Honor Guard at an election. Participation, in the way of the Soviet regime, was mandatory—but we did get to miss class, which was as desirable in that time and place as it has been for schoolchildren since the beginning of time. The fact that I was excited to be formally excused from class indicates that it must have been before I became a brazen truant, so probably fourth grade.

What election could it have been? Probably for the delegates to the local soviet (which just means “council”—there is really nothing more sinister to this word; it is also the word for “advice”). Periodically there were leaflets promoting various candidates, with their names and photos and nothing else because (1) their party affiliation was obvious and (2) so were their campaign promises.

The polling place was a school, but not ours–#57, which was in my home district (I went to a school of choice, #37. It included some children of the intelligentsia, but otherwise had very little to recommend it in the general landscape of the most stagnant decade of the country’s history). It was my first and last time inside the building past which I frequently walked on my way to and from my school (the shortcut to #37 past #57 lay past wastelands and garages, which is more than symbolic; the long way, predictably, was via Lenin Avenue).

We were supposed to do our civic duty in shifts, and in groups of four. It was a happy accident of fate that my BFF and I were the last two girls in class in alphabetical order. We were told to arrive for our shift wearing our Young Pioneers uniform. We actually had three types of uniform: brown dress and black apron for everyday, parade uniform of brown dress and white apron (which you are technically not supposed to wear as a Young Pioneer, but occasionally someone screwed up and forgot and showed up at an important event in the wrong uniform, immediately giving rise to speculation that they were kicked out of the Pioneers), and the Pioneer uniform, white shirt and navy skirt. Of course, denim skirts were not allowed—and of course, my mother sewed a super-cool denim skirt for me. The odious math teacher would sidle up to me and admonish me for wearing denim, and I would assure her that next time I would wear plain navy wool. It was our own little détente.

But that day, we were ready to represent, and I am sure that my skirt was wool, my red tie had no soup stains, and there was a giant white bow in my hair. The entire class was extremely nervous leading up to the big event, because a rumor was floating that we might have to stand stock still and hold the Pioneer salute for the entire time. Not only did that rumor turn out to be false, but we also were fed on breaks during our 2-4 hour shift: sparkling lemonade and the ever-popular “basket” cakes, though not the really delicious ones from the Volkov Theater.

https://oldladywriting.com/2020/07/26/all-my-world-is-a-stage/ Despite the fact that one of the two boys in our merry quartet was mine and my BFF’s sworn enemy whom we regularly fought on an off school grounds (in our egalitarian regime, boys and girls regularly engaged in physical combat), we had a grand time during a grand occasion.

The four of us basically just stood in a line on a dais in the school auditorium, trying to convey the motto “Pioneer is always ready” with our eager and helpful demeanors. We felt like we were entrusted with tremendous responsibility when an old woman approached us and asked for clarification on how to check off the one box on the ballot, and where to put the ballot. It could not have been her first time voting, but she either needed help because, well, age leads you there, or she wanted to make the young feel included. She was performing her civic duty. We were there to help. We felt the weight of the moment.

There was a big ballot box sitting in the middle of the room. There was also one of those polling booths with privacy curtains. One or two people used it during our shift—but why? Each ballot had only one candidate’s name on it. I asked my mother about it afterwards, and she said that it is possible to vote against the one candidate, but then you might have some explaining to do. Apparently, you also could not abstain from voting—shirking your civic duty was frowned upon, probably earning a reprimand at work from the Soviet HR equivalent.

It is easy now to say that an election with just one candidate is a sham (although I have voted in many a Western Democracy’s election where a candidate also ran unopposed). It is easy to sneer at a high voter turnout by attributing it to coercion (although if the day of election is a day off work and school ANS you get to eat and sing songs—who wouldn’t? And how is exercising your most important civic duty not a cause for celebration?).

This memory is my own, and is not an endorsement of any particular political system. I never voted in that system. I was an observer, for one brief shining moment, and it left me with a feeling of responsibility that has not left me to this day. I have seen democracy in action, and I have seen democracy fail. I remain hopeful—but only just…

Long live women, who have equal rights in the USSR!”

[1] Emily St. John Mandel, “The Glass Hotel”.