I spent four summers of my life in Crimea, in a resort town called Yevpatoria; it was love at first sight, and the kind of love you never recover from. Childhood memories burn so bright that some scenes of the movie from that era still play unbidden in my mind’s eye. We then switched to the Baltics for several reasons, none of which seemed good enough to me: easier to find a room for rent, climate not as oppressively hot, wanting to spend more time with friends and family, or maybe something else entirely. I mourned Crimea every summer in Estonia. I mourn it still, and more so as it gets farther and farther from me “through wars, death and despair”[1]. My story is small and long ago, and does not begin to compare with the pain and loss of others, but it is my own. I wish I could tell the story of my childhood in the magical land which I fear I might never see again, but I do not even know where to start. Maybe with the annual train trip, which itself was the proverbial journey as wondrous as the destination?

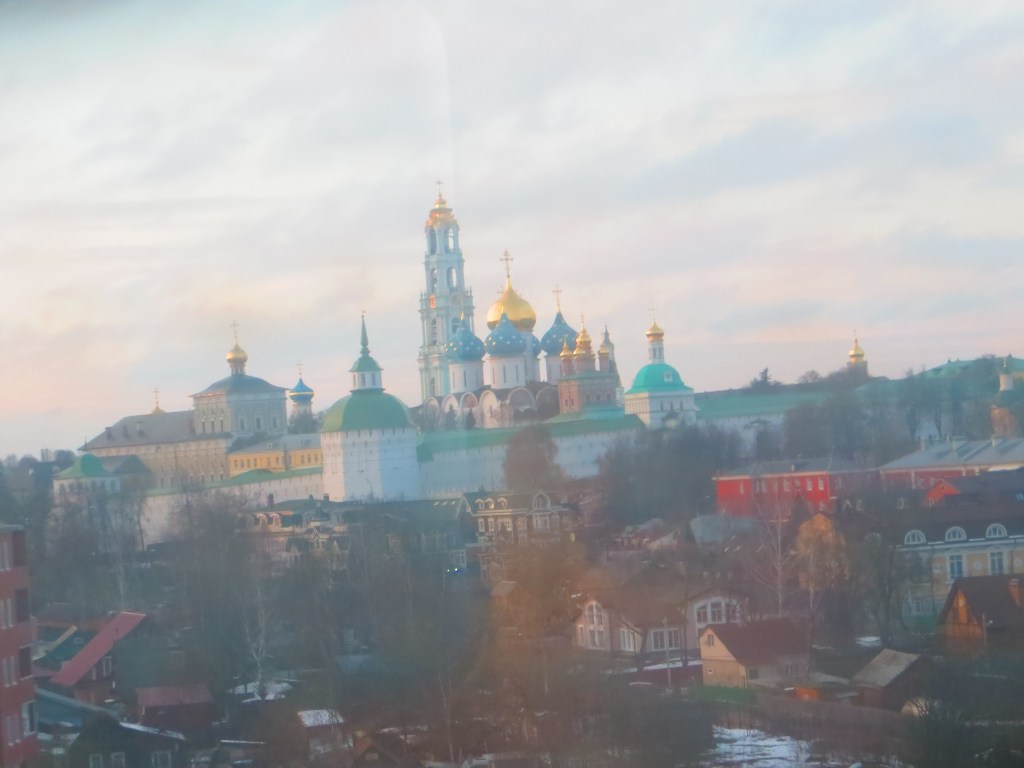

There was no direct train from Yaroslavl, of course, so first there were those four or so hours in a “suburban electric train”[2]. I always found this leg of the voyage excruciatingly boring. I had the occasion to ride it again a few years ago, and can confirm that there is still something particularly tedious about it. The big blue faux-leather chairs of old are gone, the new ones are not as spacious as they were when I was a fraction of the size I am now, and the view from the window is just as monotonous (with a tiny exception when the train passes by Sergiyev Posad).

We would arrive at one of Moscow’s nine train stations—Yaroslavsky (of course). The train to Crimea would take off from another one, Kursky. It was exciting to be in Moscow, which was huge and terrifying partially because it really is, and partially because my natal family is unusually prone to panic and aimless fuss. However, while I was always trying to assert my independence and escape from my grandmother’s watchful, and baleful, eye in our provincial town, I would become entirely risk-averse during these long-distance travels. In addition, Soviet cinematography and literature of the era was replete with fictional accounts of children lost in Moscow. Although the stories always ended well, for stranger danger was not a thing in a society extolling the virtues of communal living, I found them anxiety-inducing rather than charming. To this day, Moscow instantly turns me into a country bumpkin. But I digress.

The first year Grandma and I traveled in the regular compartment train which, as time told, was not dramatically different than European trains, with seats converting to bunk beds, four to a compartment. Occasionally, and I suspect it was simply because of availability, we rode in the strange “platzkart” wagon, a uniquely Soviet invention where there were bunks in the corridor as well and thus zero privacy. Fun fact: there is no word for “privacy” in the Russian language. I cannot imagine traveling in such a clown car now but, “c’est la vie” say the old folks, “it goes to show you never can tell”[3]. For as a child, I loved the “platzkart” setup, as it was easier to climb to the top bunk, with steps everywhere because of cramming so many people into the wagon, and because it always seemed like such a friendly throng. The only bad memory I have is when the radio in our overstuffed wagon somehow jammed while playing Carmen Suite’s Habanera for a quantity of some interminable hours; I could not hear that piece of music for years without it setting my teeth on edge, and have managed to stealthily avoid the entire opera.

There would have always been a dining car, but of course we never visited such a frivolous establishment. We brought our own food, like everyone else: canned sprats in oil, black bread, boiled eggs, tomatoes, cucumbers, and salt wrapped in a piece of paper. The conductor sold tea served in cut glasses with silver holders accompanied by sugar cubes. Back then, sugar cubes seemed less fashionable than loose sugar, but now the sheen of nostalgia makes those hard blocks seem so retro cool.

It was a day and night’s journey across the land. Without video stimulation of any kind, the entertainment consisted of eating, playing cards, reading glossy Soviet magazines like “Working Woman” or “Little Flame”, and looking out the window at the landscape gradually changing from north to south. In the corridor, the windows had these little white curtains that said “Crimea” in light blue cursive letters. I was always too short to lean on the curtain rod, and eventually too tall to fit under it, but I could stand there and stare out in wonderment for as long as my grandmother would let me.

We never said “we are going to Crimea”, we said “we are going to the South”. It was universally understood, same as where I live now, everyone knows the meaning of “Up North”. Everyone was going on vacation; no one was going home.

There was a granite plate built into a cliff, proclaiming “Glory to the heroes of Syvash”[4], commemorating events of the Civil War we never studied in school, which just added to the mystery of the land. I looked for that granite plate every year, because I knew that once I saw it in the morning, I was in a different world. Waking up in Ukraine, we saw idyllic white daub huts instead of our dark log ones, forests changing into fields, pale bluebells becoming blood-red poppies. We were coming from the land of asphalt and dusty ash trees, constant strumming of trams, crowded streets. And then the train just stops, giving the passengers a few enchanting minutes in a field of poppies, imagine that!

The following day would bring Black Sea with its friendly and nonlethal jelly fish, packets of little salty shrimps sold right on the hot sand of the beach, cafeteria “Kolos” with its delicious blintzes filled with sweet cottage cheese or ground beef, Frunze park with its exotic cypresses and statues of fairy tale characters, local history museum with two cannons in the front and a tiny zoo with a monkey in the back. My grandmother then was younger than I am now, and we were going to the South for an entire summer on the beach. As an adult, the longest vacation I have ever taken, since age 19, was the trip to, ironically, Russia (11 days). A summer on the seashore has not been a part of my reality in adulthood.

Curiously enough, I remember nothing at all about the train rides to Estonia in the subsequent summers—not a single thing about the view from the window, people we met along the way, nothing at all. It was still a summer by the seashore, but no longer the trip of wonders to one of the Seven Seas.

To be continued…

[1] Quoting “Anthem” from “Chess”.

[2] I had to look up the translation. The Russian word is “elektrichka”.

[3] Quoting Chuck Berry.

[4] Alas, I cannot find any photographic proof of its existence—the plate, not the battle.